SIRU 2.0 Case: Orange Sky

SIRU 2.0 is financed by by Tillväxtverket with EU funding, and by Region Jönköpings län.

Finding a home under an Orange sky

Homelessness in Australia and Sweden

Out of a total population of 26 million, the number of homeless in Australia is 135,000. In Sweden, the number is approximately half that with around 32,000 identified as homeless in 2018. The complexity of people’s subjective experiences, differing climates and structural causes of homelessness makes it difficult to compare the details of these facts across national borders without a detailed assessment of the varying definitions and unique factors that pertain to each country. However, there are also many similarities between Australia and Sweden such as their standards of living, democratic and welfare institutions and their strong traditions of social innovation and developing new approaches to dealing with chronic social issues. The following presents the case of Orange Sky, an Australian for-purpose social benefit organization that has developed a range of creative responses to homelessness. The case is presented with the aim of showcasing opportunities for cross-learning and knowledge transference on homelessness alleviation and, more generally, on building community connection with people living in these vulnerable situations.

The Orange Sky Organisation

This case summary tells the story of Orange Sky (OS), a for-purpose, volunteer-based business that primarily offers laundry service to people who are homeless. OS was established in 2014 in Brisbane, Australia. Orange Sky is the world’s first mobile laundry service for homeless people and was founded by Lucas Patchett and Nicholas Marchesi who have been awarded numerous honours and awards including Young Australians of the Year in 2016 and the Order of the Medal of Australia in 2020. Beginning with a single van and two washing machines provided by a local white goods retailer, Orange Sky has since expanded to be an international organization (as it now operates now in New Zealand) that in the last year has supported 13,700 people, washed 35,159 loads of laundry, provided 6,360 showers, held 67,658 hours of genuine conversation, and provided $9.5 million AUD in social impact.

How it all began

In 2014, 20-year-old friends Lucas Patchett and Nicholas Marchesi deferred their degrees and quit their jobs to start a mobile laundry service for homeless people. The “crazy idea” (Orange Sky Australia, 2020) had been stimulated in part from Marchesi’s mother who was a volunteer in a local church food van for homeless people in Brisbane in Australia. They called their social business “Orange Sky” after the title of Marchesi’s favourite song by the songwriter Alexi Murdoch. After appealing to the good graces of a local white goods operator, the two renovated a van, which they called “Sudsy”, into a mobile laundry van. As the young entrepreneurs were building and experimenting with their mobile laundry van they weren’t sure what reaction they would get. Most people who found out what they were up to said it was a “crazy idea”. After several mechanical setbacks they drove Sudsy to a park where food was being given out to homeless people. At first there was confusion as no one had come across such a thing as a mobile laundry for free. One person, Jordan, had all his clothes in a backpack and was willing to give it a go. Lucas chatted with him while the washing machine did its job and he was amazed to learn that Jordan had completed, some eight years earlier, the same engineering course Lucas had recently deferred from. Somehow things had gone badly for Jordan. He had lost his job and without family support had ended up on the streets. Jordan spoke to them about all this and much more while his laundry was being done.

That night Marchesi and Patchett reflected on their day’s experiences and realized that their crazy idea would provide a much-needed service, but they also came to understand that it was going to provide something more as well. They saw that the business of washing laundry was not the only benefit their service could provide to homeless people. They were also providing something perhaps even more essential than doing the laundry. After their meeting with Jordan, from that night on, they always carried six chairs with them in their vans for their “conversations with friends”. Jordan had shown Nic and Lucas that a one central problem facing homeless people was the lack of social connection. The need for conversation and reconnection is a social need that homeless people across the world share. On that first day Nic and Lucas found out, with Jordan’s help, that doing the laundry and having non-judgemental conversations were going to be the two central pillars of the Orange Sky mission.

Adaptive innovation

Providing mobile services for vulnerable, homeless people is an innovative idea but, as is often the case in social innovation, there were other unintended consequences to offering the service. The most immediate consequence of doing the laundry was that Lucas and Nic had to talk to their homeless friends while their laundry was being washed and dried. There was literally nothing else to do for an hour and so they chatted and talked about everything under the sun with their new contacts. This connection opened a new and adaptive realm of understanding their idea that they had not thought about. They were not primarily in the laundry business but the business of conversation and social reconnection. As their annual report highlights:

“The important thing to remember about all of these moments and numbers is that it always boils down to the same thing; the people, stories, conversations and connections that take place on orange chairs.” (Orange Sky Australia, 2021)

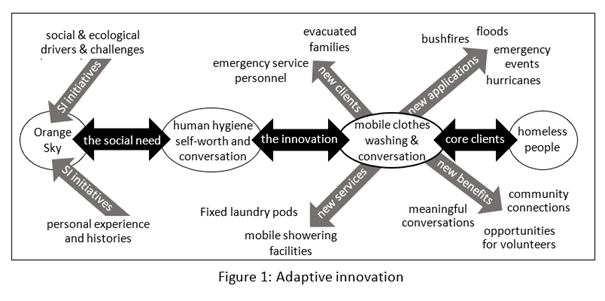

The core features of Orange Sky’s success are the clarity of their mission, the direct human response and practical simplicity of meeting a previously unrecognised human need, and enabling community bridging and engagement through social reconnection. Figure 1 depicts some of the core elements of the evolution of the innovation process that Orange Sky underwent in its development. The figure depicts that OS services are flexible and responsive to the expressed needs of the service users and this builds an organizational culture that responds innovatively to different situations and populations. OS now offers mobile laundry services to those affected by emergency events such as floods, bushfires or storms where communities need emergency mobile laundry services because of precautionary evacuations and as a result of the emergency itself rendering people homeless. It is not only the victims of events that need emergency laundry facilities but the service personnel, first responders and emergency teams, that need these services.

Core social innovation takeaways from the Orange Sky case study

There are unique and important aspects to the emergence and success of Orange Sky Laundry that might serve as inspiration or even as a model for developing social innovations to meet personal and community needs.

Integrative service responses to core human needs

The social innovation of Orange Sky is a service that responds to three fundamental human needs – physical hygiene, self-worth, and human conversation. In other words, Orange Sky provides a direct and practical response that meets an objective need (hygiene), a subjective need (self-worth) and a relational or inter-subjective need (conversation). Any social innovation that does this will provide a powerful contribution to people’s lives.

Co-testing and prototyping on the run

The idea of doing laundry is a simple one that could immediately be tested. As soon as the original prototype was made and trialled, further innovations followed. Idea and action, testing and service prototyping went hand in hand. The learning here is that on-the-ground testing can take place in real situations when the need is recognised by the community and the client group.

The power of formative experience

The origin of the Orange Sky social innovation is a powerful example of how early formative experience can be crucial for the conception of the initiative. Young people can use their experiences and energy to innovate in powerful and direct ways in response to fundamental human needs.

Continuous innovation from a constant vision

The ongoing innovation that characterises Orange Sky’s growth does not mean that its founding vision is weakened or compromised in any way. The heart of the business – to do washing and to have “awesome chats” – is still very much the central operational activity and the volunteers, public donors and, most importantly, the service users still recognise the genuine continuity of this core value.

The integration of values and action, conversations and technology

A notable feature of the service is its capacity to integrate (in the sense of embracing difference) and quickly include varying perspectives and voices. Most obviously this was seen in their integrative response to the need for conversation which their homeless friends expressed immediately during the first day of operations.

Partnerships with community

It is a cliché in social innovation to talk of partnerships but all cliches are built on a core truth. One of the most powerful characteristics of the Orange Sky organization is its focus on building collaborations and partnerships across government, private, not-for-profit and community sectors. More than this though is the depth of those partnerships and that they are built on a kind of joy in opening opportunities for partners to contribute and express their wish to help and share.

Some further questions

This case invites some further questions on how knowledge and learning and be transferred and translated into the local situation of social innovation and its development. Among many candidates, these questions include:

- How can communities be supported to develop social innovations that need very little initial physical or financial resources but significant moral and emotional resources?

- What is the place of happy and unintended consequences in the development of social innovations and how can we notice and record them?

- Is the notion of adaptive innovation something can be considered in greater depth and how might it inform local social innovations?

Extra resources and references:

- Orange sky website External link, opens in new window.

- Orange sky annual reports External link, opens in new window.: Orange Sky Australia. (2021). Orange Sky Annual Report 2019/20. Brisbane, QLD: Orange Sky Australia

- Nic Marchesi, one of the founders of Orange Sky, was interviewed on the podcast The Decade. You can listen to it here